There has been a significant decline in interest in politics among Hongkongers, according to a Chinese University survey from the Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies last month. 62.9 per cent of respondents reported that they were not very interested, or not interested at all, in politics – a decline of 7.4 per cent.

The survey also found that 84.7 per cent of respondents rarely or never used social media such as Facebook to discuss politics, an increase of 8.8 per cent.

The survey revealed that citizens – in increasing numbers – perceive that government officials do not care about their views (55 per cent, up from 47 per cent in 2022) and that they have no say in government policies (51.9 per cent up from 43 per cent in 2022). The poll also records an increase in the much smaller numbers who perceive that government does listen and that they do have a say (now 16 per cent and 25 per cent respectively), signalling increasing polarisation.

Hongkongers generally perceive that our local political parties can neither hold the government to account nor represent a diversity of citizens’ opinions. The findings taken together paint a depressing picture.

“Politics’” concerns the exercise and distribution of power. Basically who gets what, when, and how. The wealthy in Hong Kong have always been politically active, advancing and defending their interests where the stakes are huge. Their power is reflected in our political institutions, for example, in functional constituencies in the legislature. The polls mostly focus on the rest of us. And they seem to say that many of the rest of us are increasingly turning away from the rough and tumble of exercising power.

These results need context. First, trust in government, although recently rising, is still relatively low (less than 30 per cent in one March 2023 survey trust the government). Moreover, in recent months, the popularity of the government has also declined. If we take a longer view it is clear that Hongkongers have for long valued freedom and prosperity more than democracy.

Since 2020, however, residents appear to value freedom, prosperity and security and the rule of law in equal measure, indicating some success for authority’s campaigns to implement the national security law. Democracy, perhaps a proxy for participation in politics, lags relatively far behind. Other polls also reveal a polarised Hong Kong on these issues.

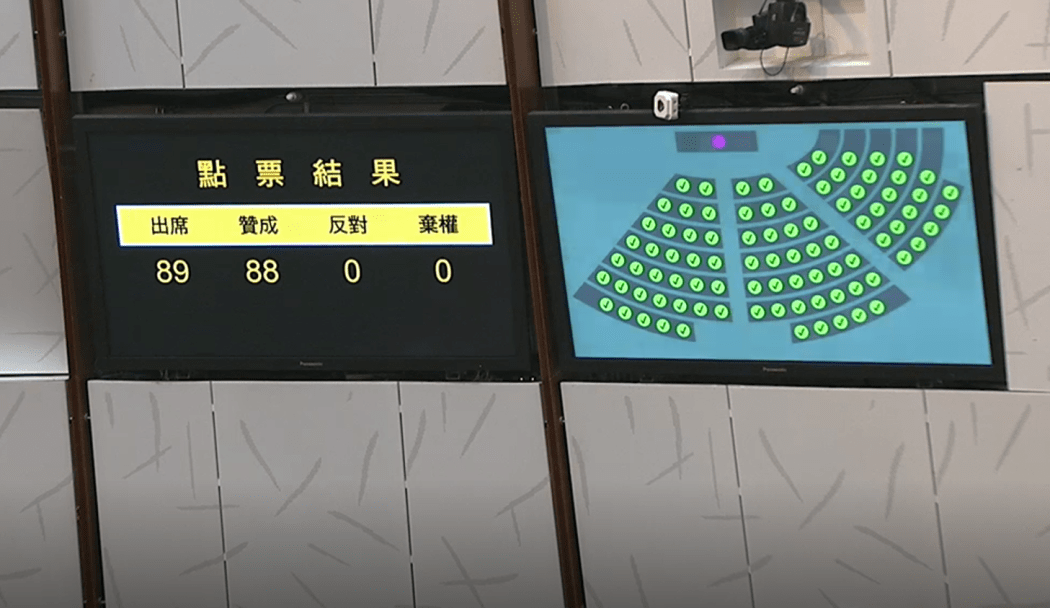

Second, central and local authorities have imposed a new political system in Hong Kong that severely restricts formal political participation in the legislature and district councils. Hongkongers understand this. Of what use is politics for the average person in the new setup? they may be asking.

Hong Kong’s new executive-led system also reduces the autonomy of the legislature. May lawmakers on their own now vote against the budget? May the legislature, on its own, set up select committees to investigate the government and hold it to account? Previously both were possible. Do these actions now need the approval or instruction from the central authorities relayed to members through the office of the Chief Executive? It would appear so.

Another reason citizens may perceive that local political parties and contacting officially selected politicians to be relatively worthless. A rational perception, you could argue.

Third, it is not surprising that Hongkongers perceive that using social media to express political views carries considerable risk. Authorities continue to arrest citizens for their social media posts. Still, pro-establishment figures are avid producers of content and consumers of social media. This indicates again the polarisation of Hongkongers. Remember that pan-democratic supporters among our citizens regularly polled at least 40 per cent, often more.

Fourth, central and local authorities continue to campaign against the vaguely defined “soft resistance” in ideology, culture, education, and the media, warning ominously that unidentified anti-China forces are trying to make a comeback. No specifics. Stay away from politics, it’s too risky, many may be saying.

Academics described Hongkongers in the 1970s and 1980s as politically apathetic and unwilling to engage in politics, valuing the pursuit of family-centred economic benefits. This view overlooked informal political activism and mobilisation that has long been a part of Hong Kong political culture. In the 1980s and 1990s, authorities expanded formal political participation, eventually even in the legislature – a trend that continued post-1997.

Most of us in Hong Kong are citizens of China. Citizenship requires our active and informed participation. Our political institutions provide formal channels for participation, such as through elections of legislative and district council members. When citizens perceive that these formal channels fail to consider their interests, whether these be livelihood issues or democratic and accountable government, citizens go outside these channels to speak to authority. Hong Kong has a long history of political activism and protest.

With much more limited formal channels for participation, will Hongkongers turn to protest as they have in the past? Officials are making this option much more difficult. The right to protest and demonstration is guaranteed in the Basic Law, but the exercise of this guarantee depends on what happens on the street, in practice. So far, authorities have strictly limited citizens’ ability to organise protests using tools such as the law, administrative procedures and intimidation.

Of course, dissatisfied citizens in Hong Kong may leave. Since 2020, tens of thousands of Hongkongers have emigrated. Since 2020, Hong Kong has also welcomed thousands of mainlanders. Polls indicate that those mainland born are more confident in Hong Kong’s future and more positive about their life in Hong Kong than native born Hongkongers. They may also have a different understanding of their political rights than do native born Hongkongers. China’s constitution and the Basic Law “guarantee” citizens’ rights using exactly the same language, undoubtedly with different meanings. Officials welcome this informal “renewal” of Hong Kong’s population. It undoubtedly makes their life easier.

Authorities have launched a multi-pronged campaign to change Hong Kong’s political culture. It consists of patriotic education and activities in schools, silencing opposition politicians, and shuttering opposition media. Dumbing down people’s expectations of participating in politics is part of the strategy. Authorities apparently perceive that once the genie of political participation, a defining characteristic of citizenship, is let loose it can be stuffed back in the box and they are working overtime to do precisely that. As we have seen the poll results quoted above indicate some official success.

It is in this context that the Democratic Party has apparently decided to field candidates for the upcoming new-look district councils. If they succeed (that is, pass official vetting) then in the words of Lau Siu Kai, they may become “recognised patriots”. Apparently patriotism is less about what we feel and more about official recognition and approval of our behaviour.

Authorities are keen to accurately identify friends and enemies in Hong Kong. That is what united front work is all about. This focus does not particularly value social cohesion, although that would be nice. We are still waiting to see how much diversity of opinion authorities will tolerate. Hopefully more and not less. Stability in Hong Kong depends on it.

Support HKFP | Policies & Ethics | Error/typo? | Contact Us | Newsletter | Transparency & Annual Report | Apps

| HKFP is an impartial platform & does not necessarily share the views of opinion writers or advertisers. HKFP presents a diversity of views & regularly invites figures across the political spectrum to write for us. Press freedom is guaranteed under the Basic Law, security law, Bill of Rights and Chinese constitution. Opinion pieces aim to point out errors or defects in the government, law or policies, or aim to suggest ideas or alterations via legal means without an intention of hatred, discontent or hostility against the authorities or other communities. |

Help safeguard press freedom & keep HKFP free for all readers by supporting our team

More HKFP OPINION:

HKFP has an impartial stance, transparent funding, and balanced coverage guided by an Ethics Code and Corrections Policy.

Support press freedom & help us surpass 1,000 monthly Patrons: 100% independent, governed by an ethics code & not-for-profit.